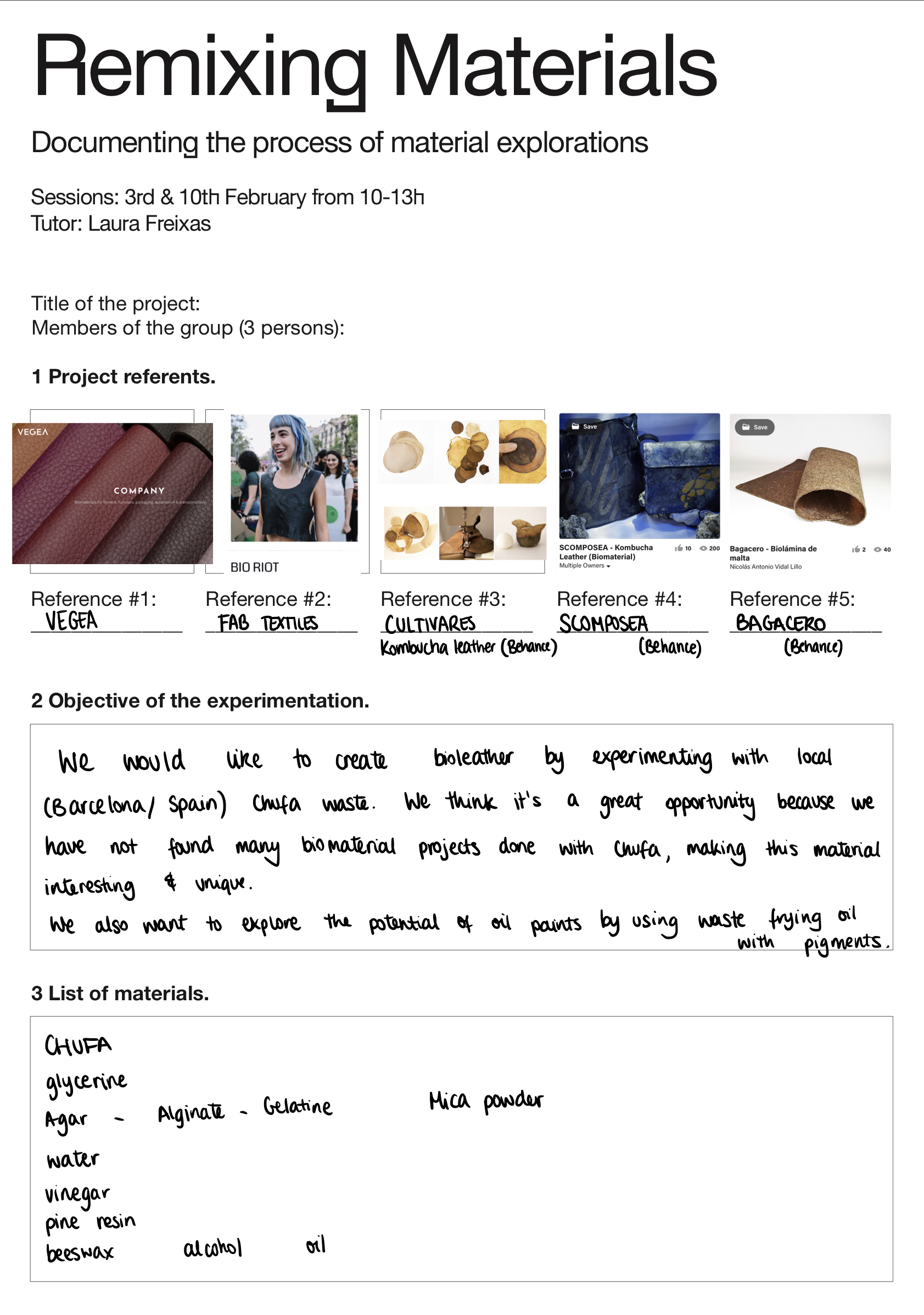

Remixing Materials II

Materials in Context

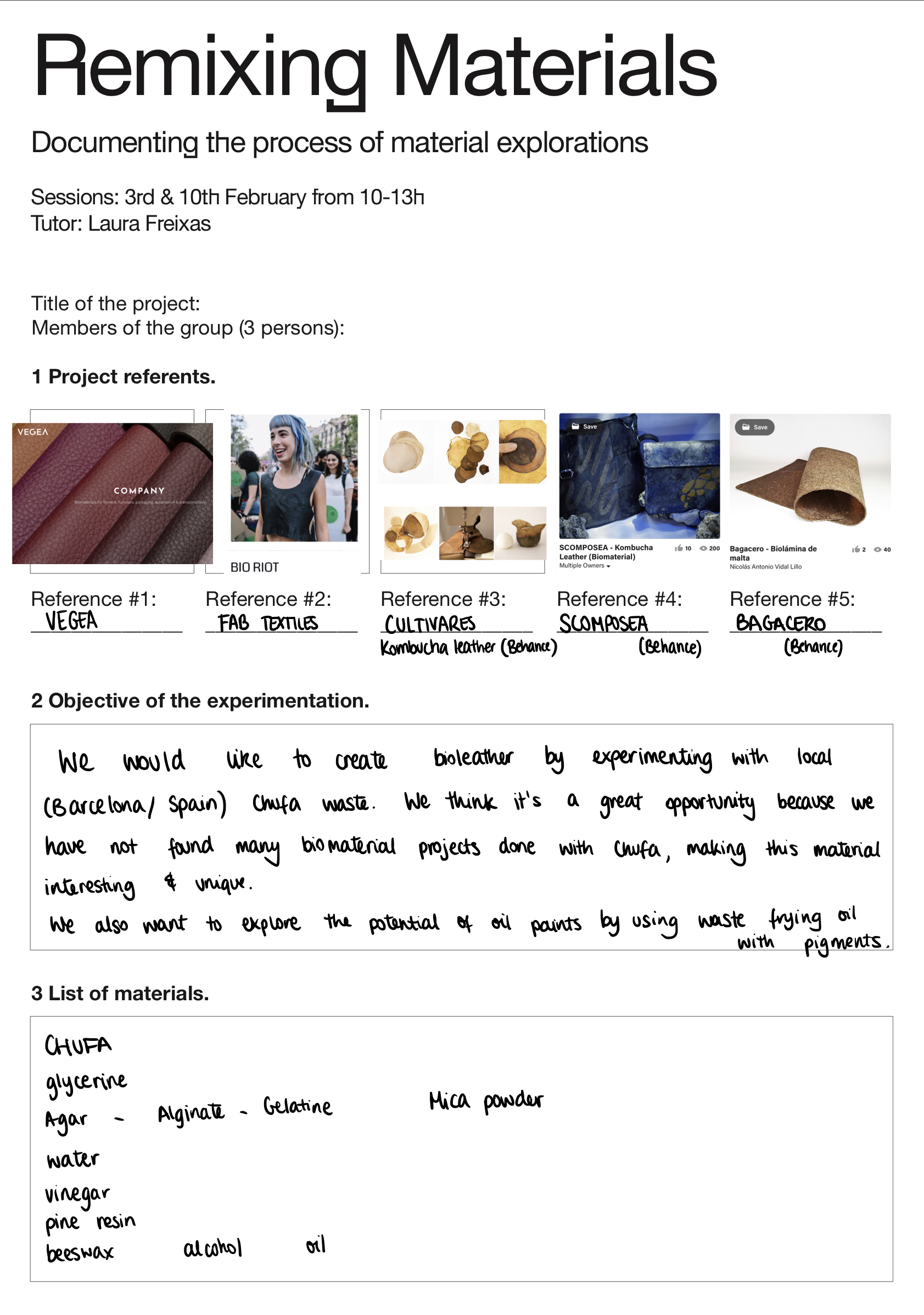

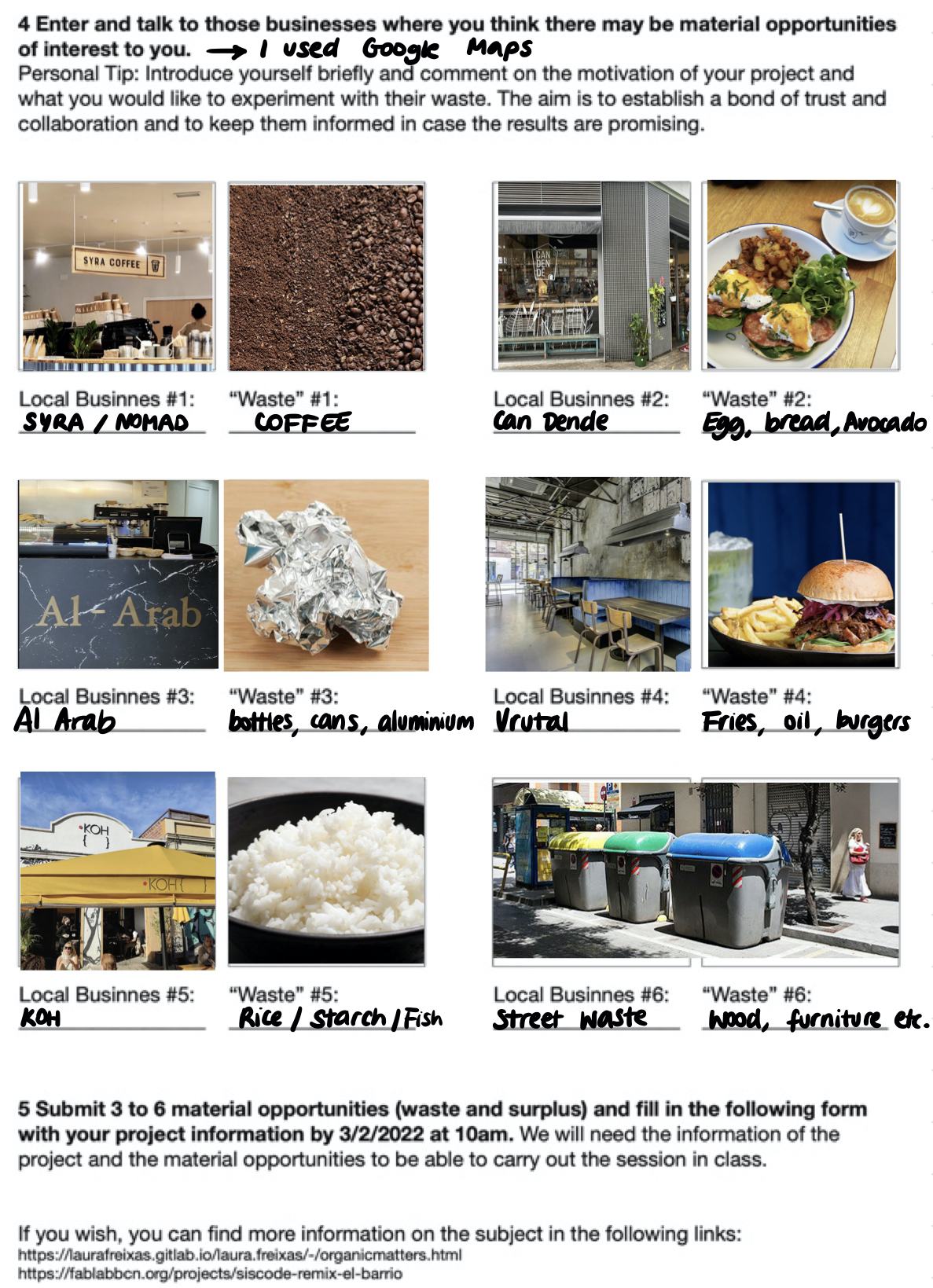

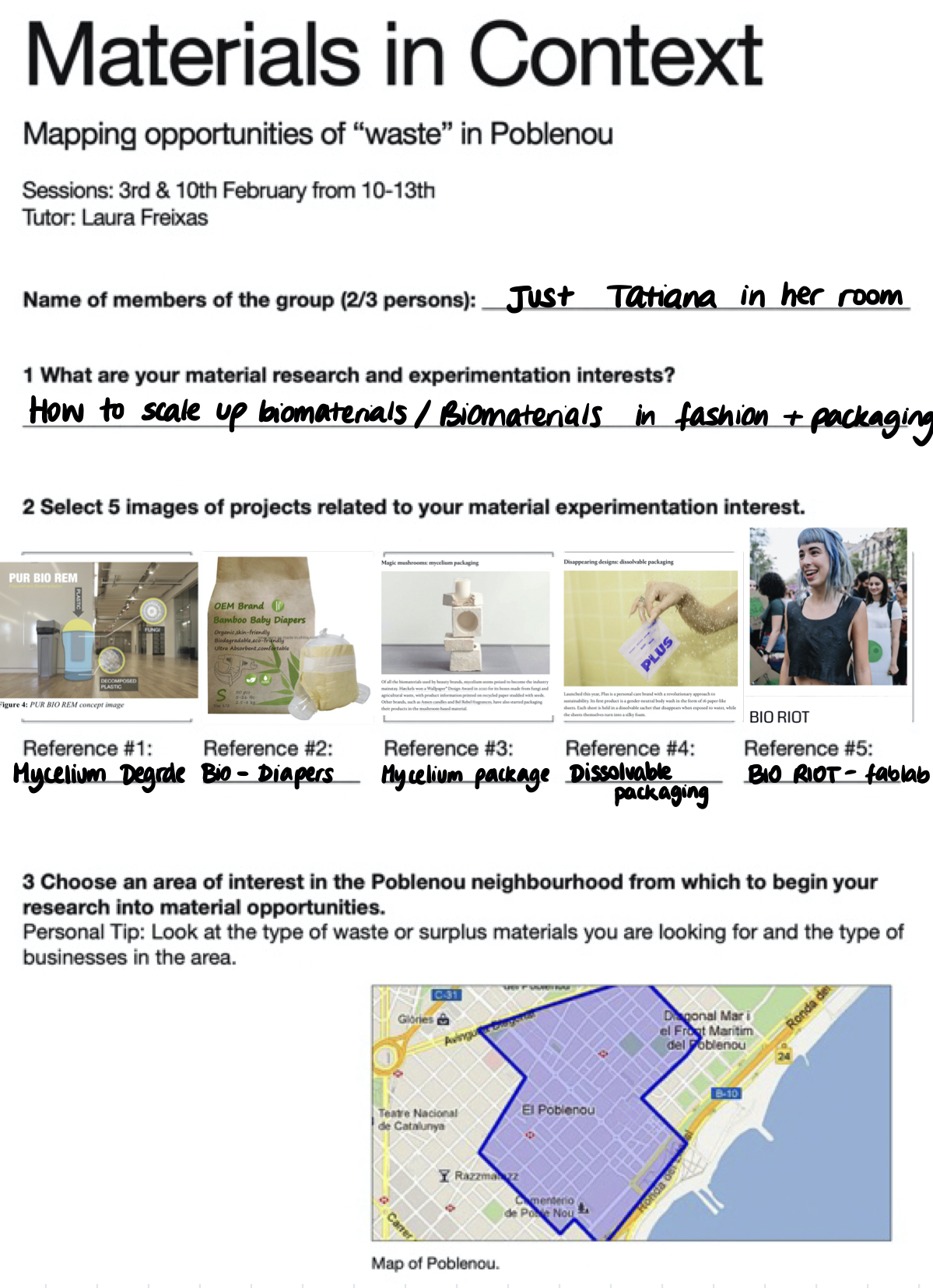

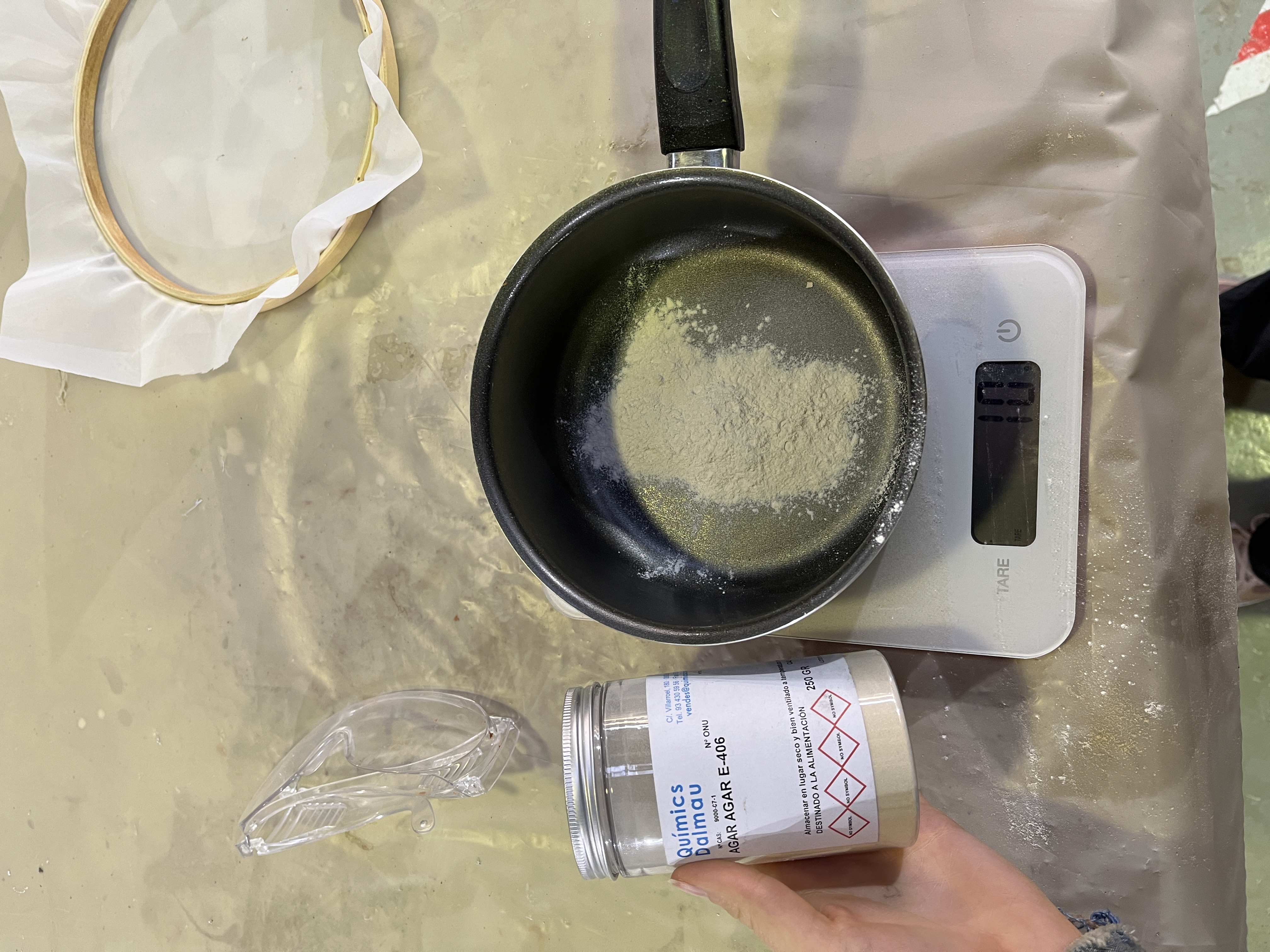

It was hard for me to complete this exercise in the way which Lara planned us to, because I was still in quarantine in my room, unable to visit the restaurant & shops in person. Therefore, I used Google Maps and tried to located businesses I already knew, but also tried to find something new. I did not only select biomaterials

I am not sure what materials I would like to experiment with specifically, but I do know that I would like to find practical projects that could also be scalable.

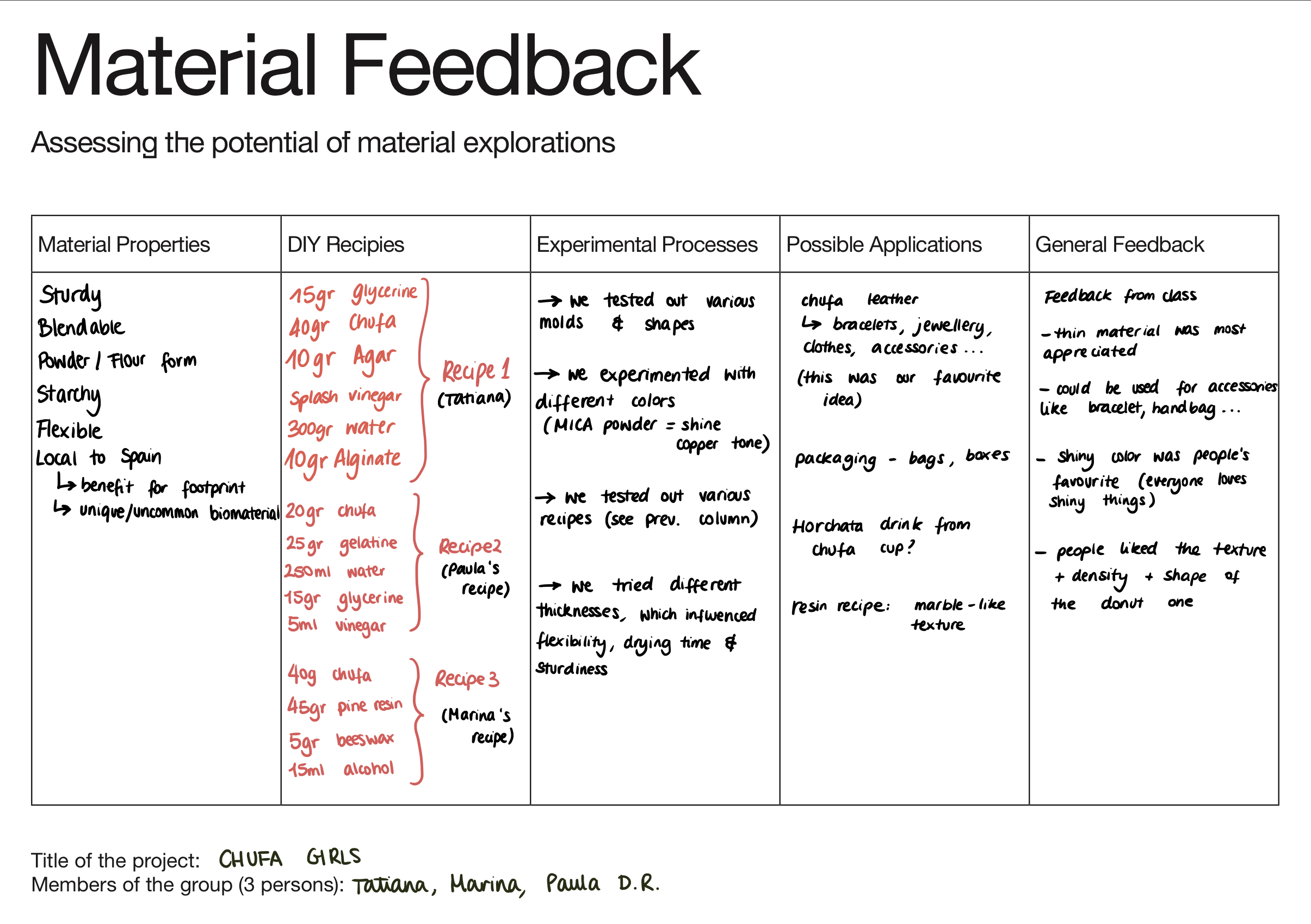

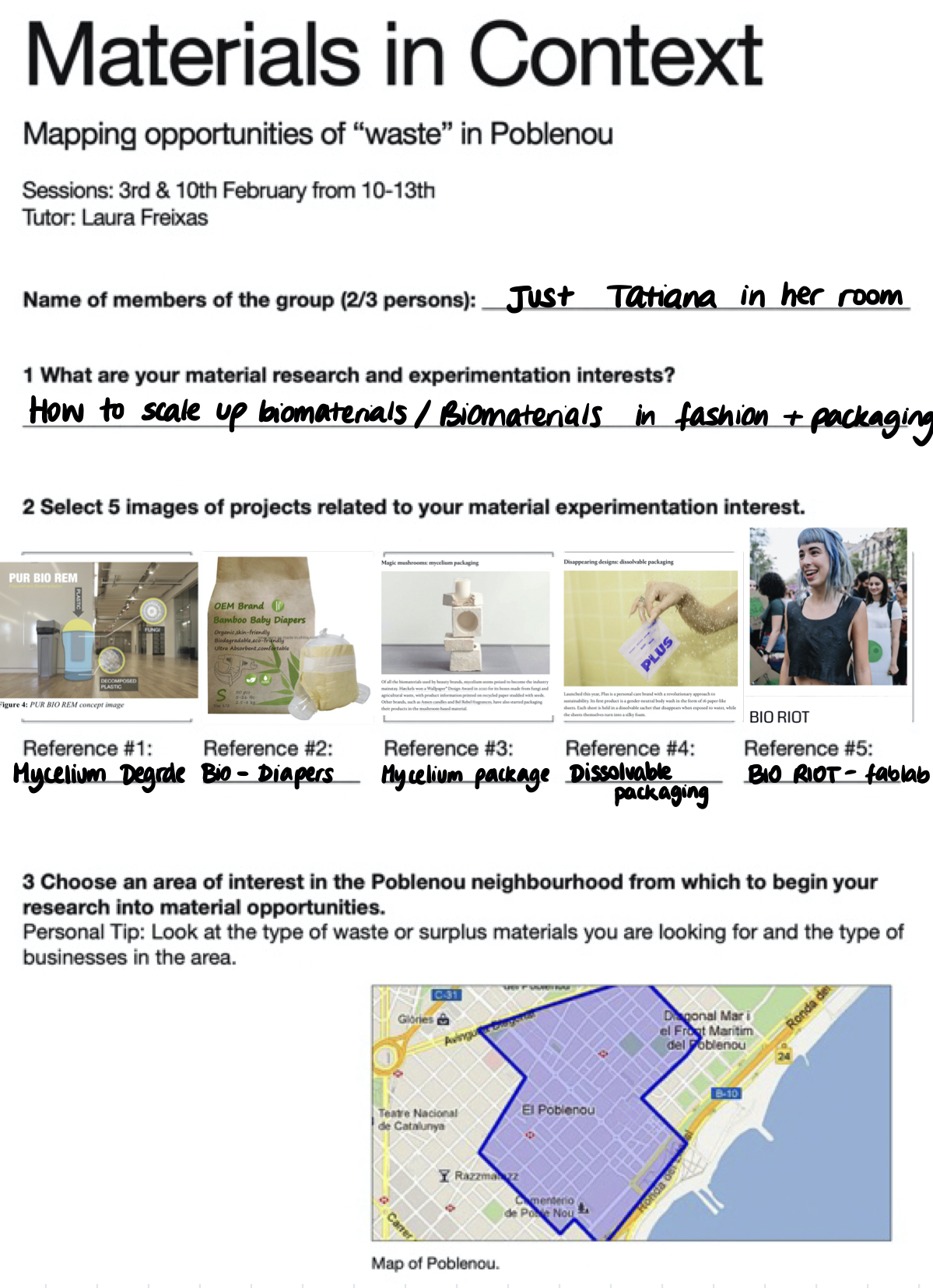

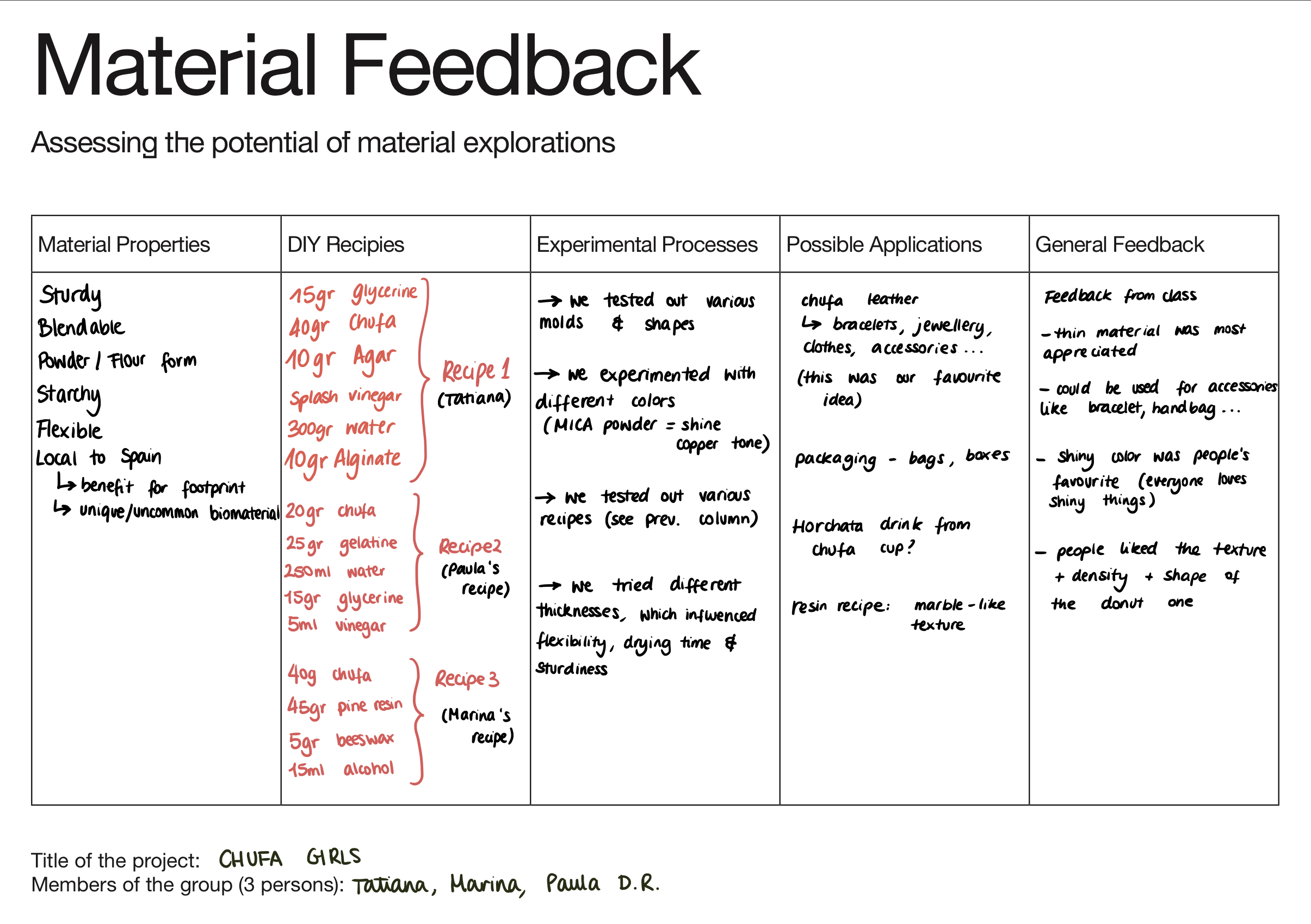

Here is the exercise sheet that Laura asked us to fill in:

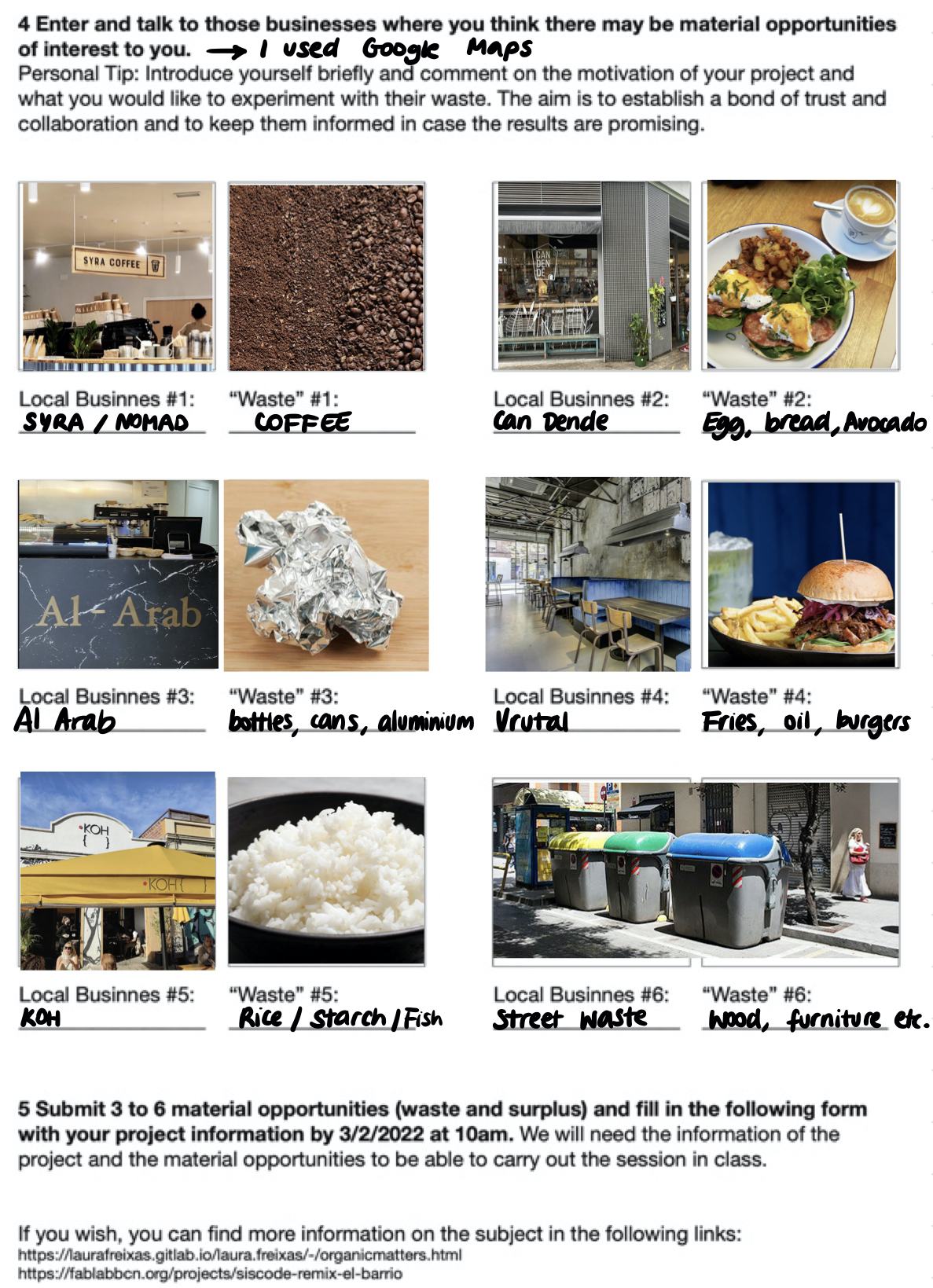

On Thursday, I joined Paula & Marina’s group through a Whatsapp call whilst they were in class. We shared our Poblenou waste maps and exchanged ideas and resources. The Horchateria and Burger restaurants ended up interesting us the most, so we decided to explore the two main materials those businesses could offer: Chufa (tigernut) and Oil.

Chufas:

Chufas:

strong, chewy, malleable, resistant, starchy, blendable

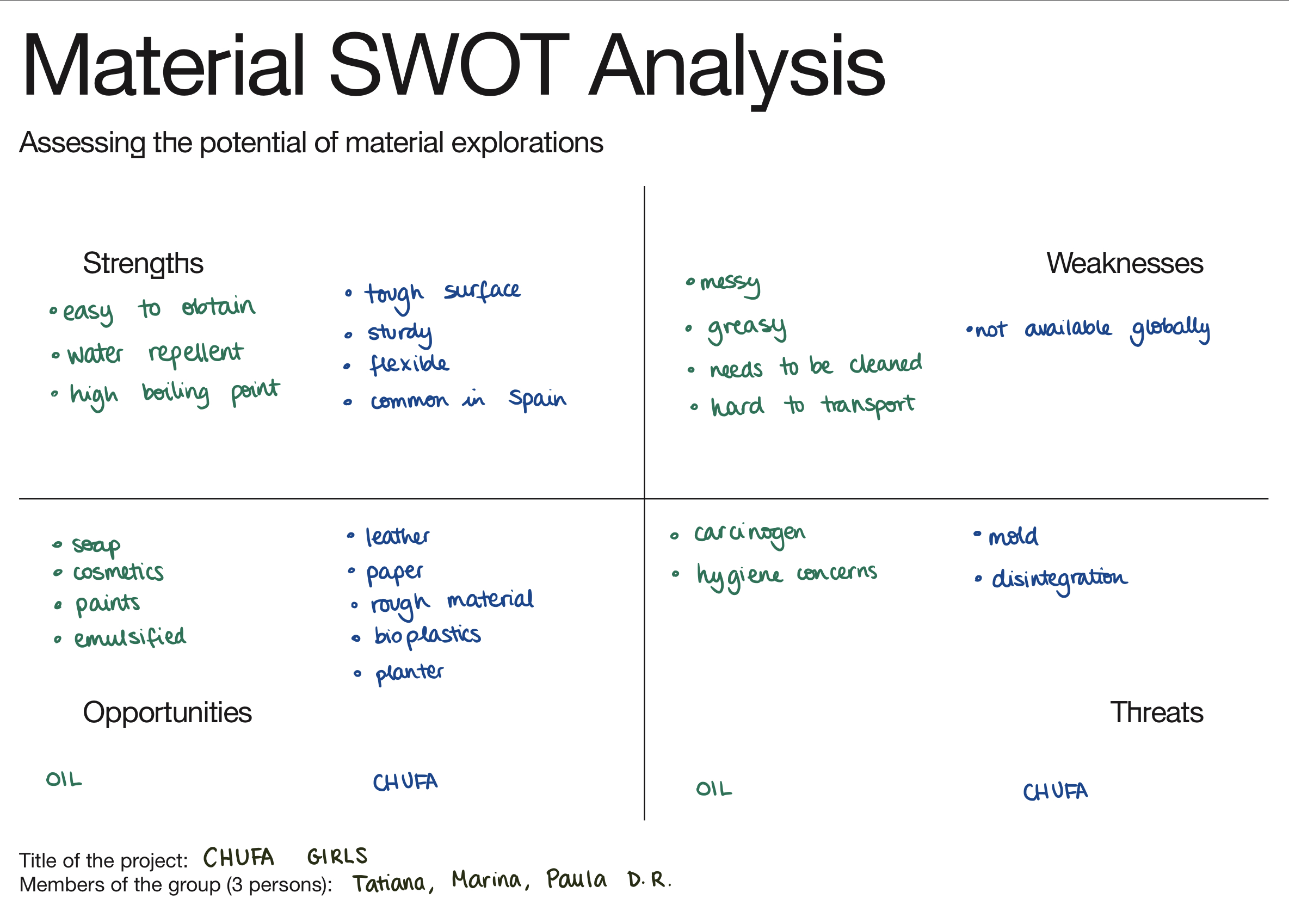

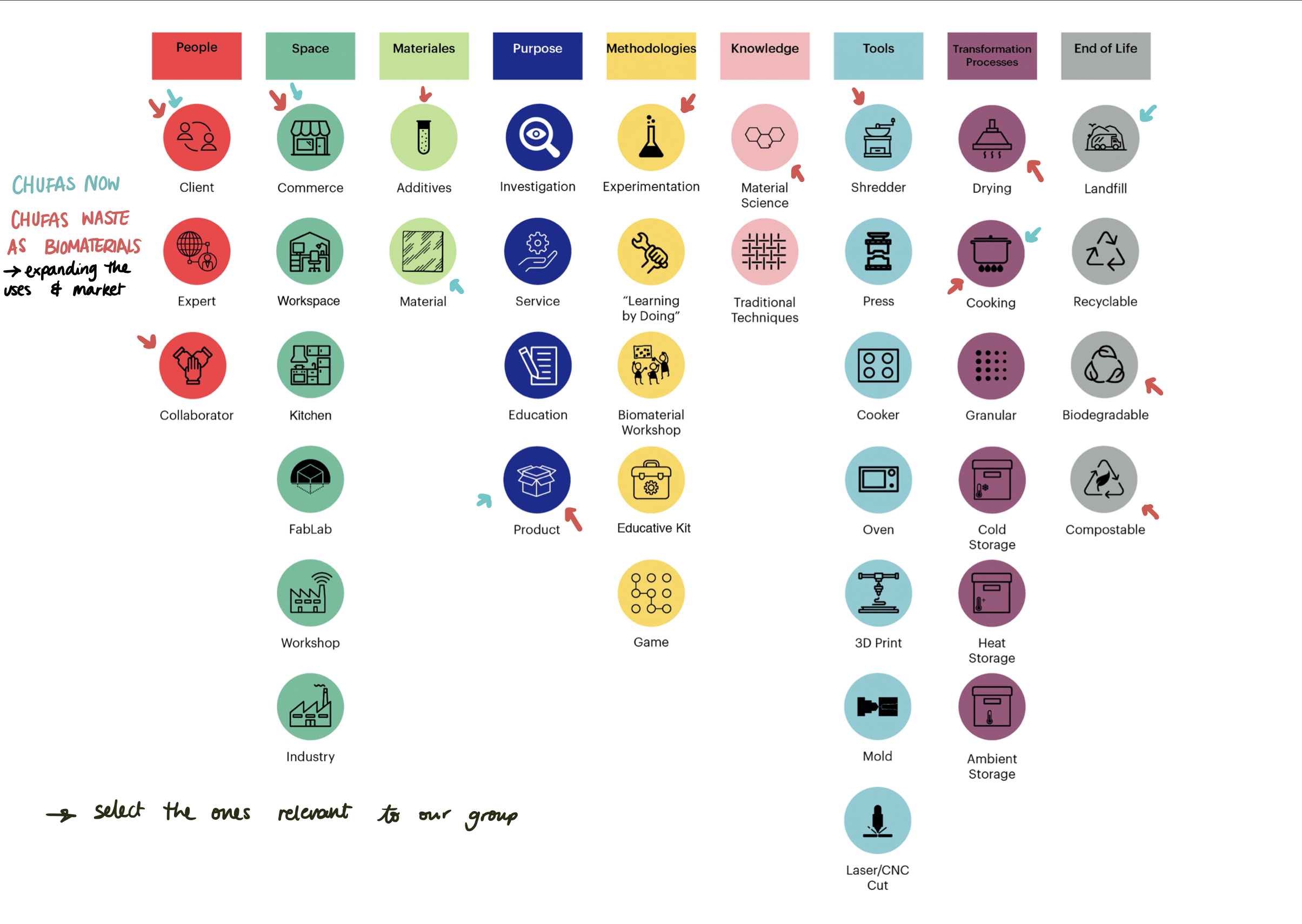

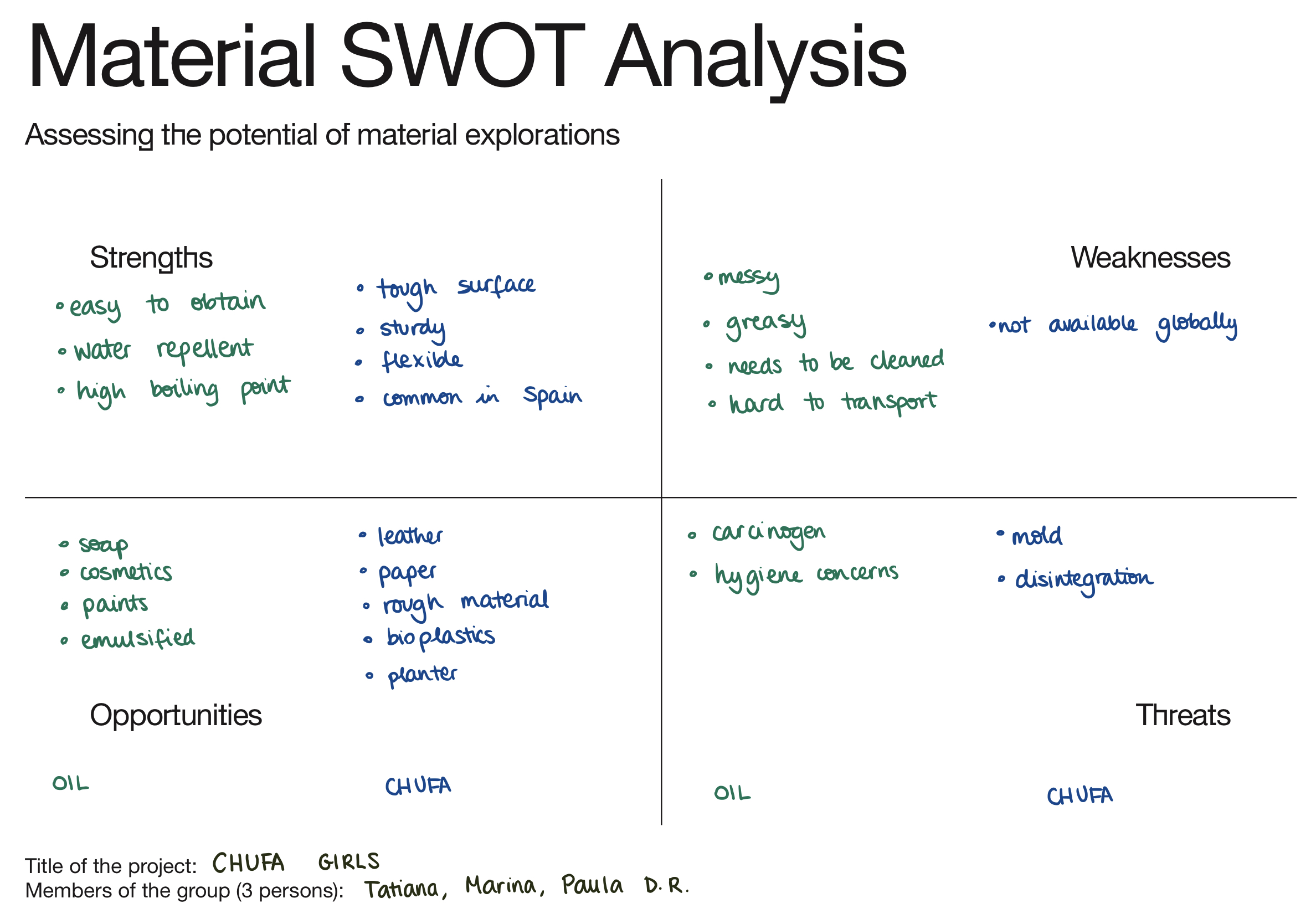

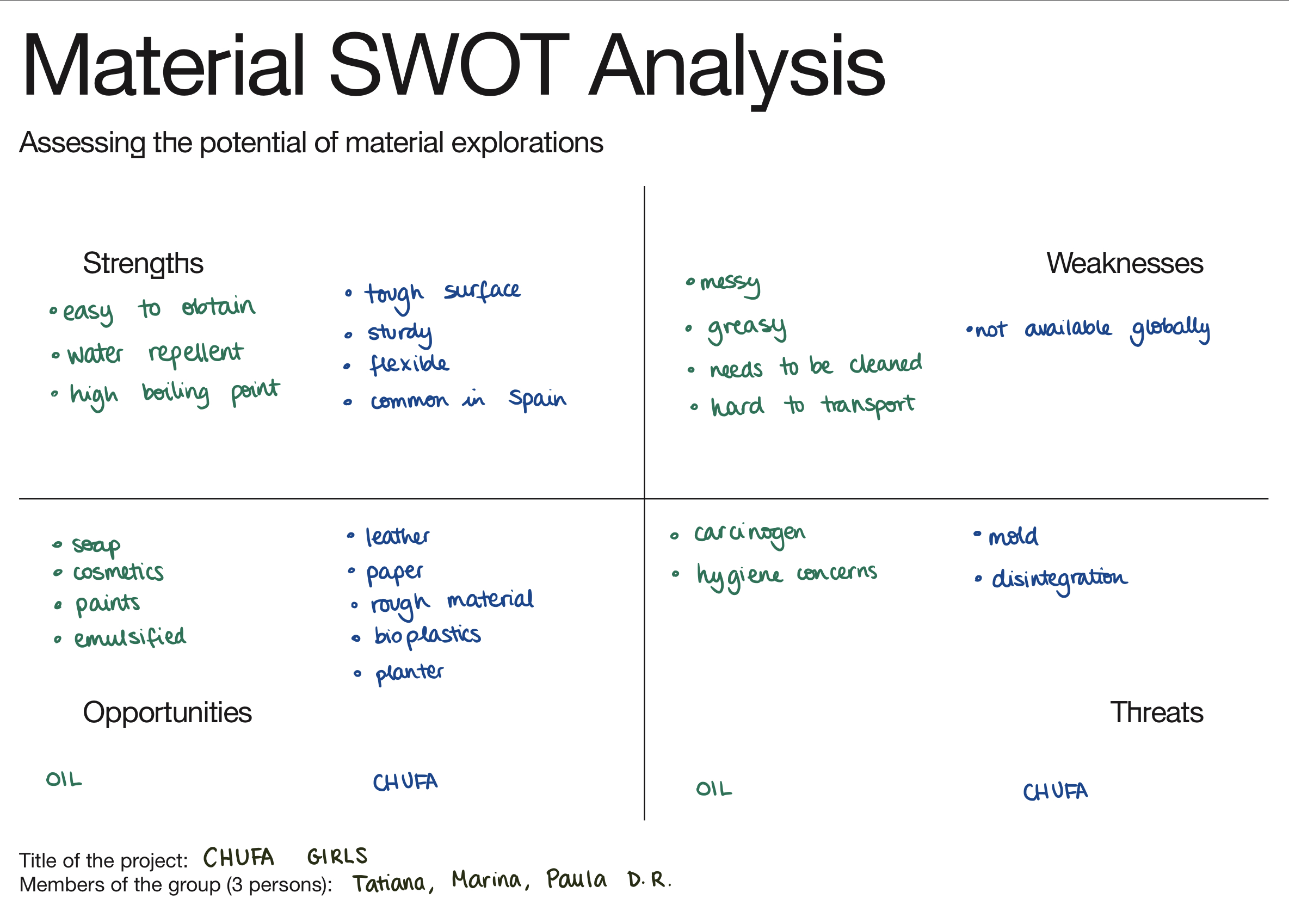

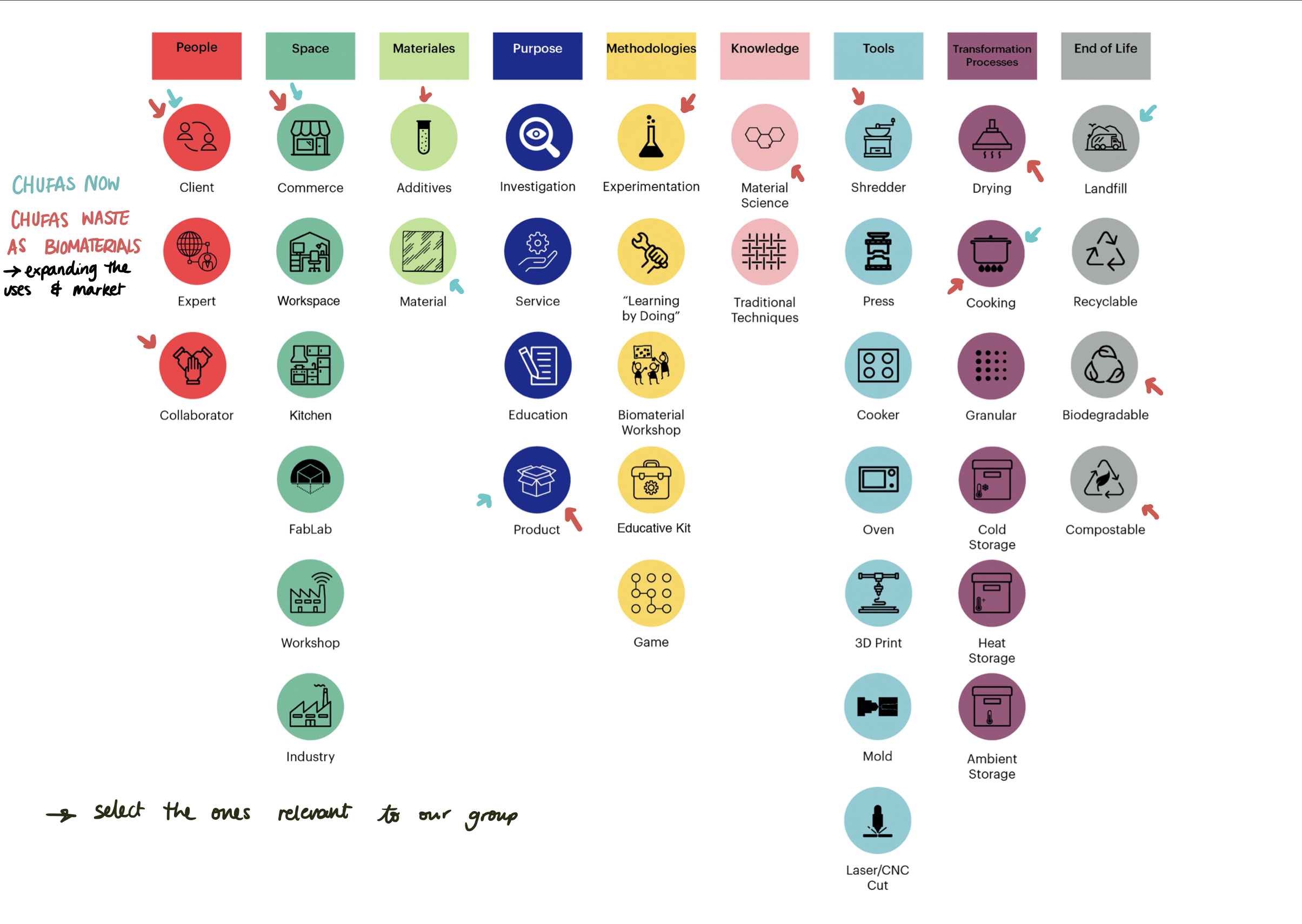

We evaluated the uses, strengths and downfalls of each material, and how they could be used in application. Some initial ideas that came to mind were making plant based leather out of the tiger nuts and making paint by mixing the oil with waste pigments. We began to do research on both opportunities, and returned to the businesses to collect their materials.

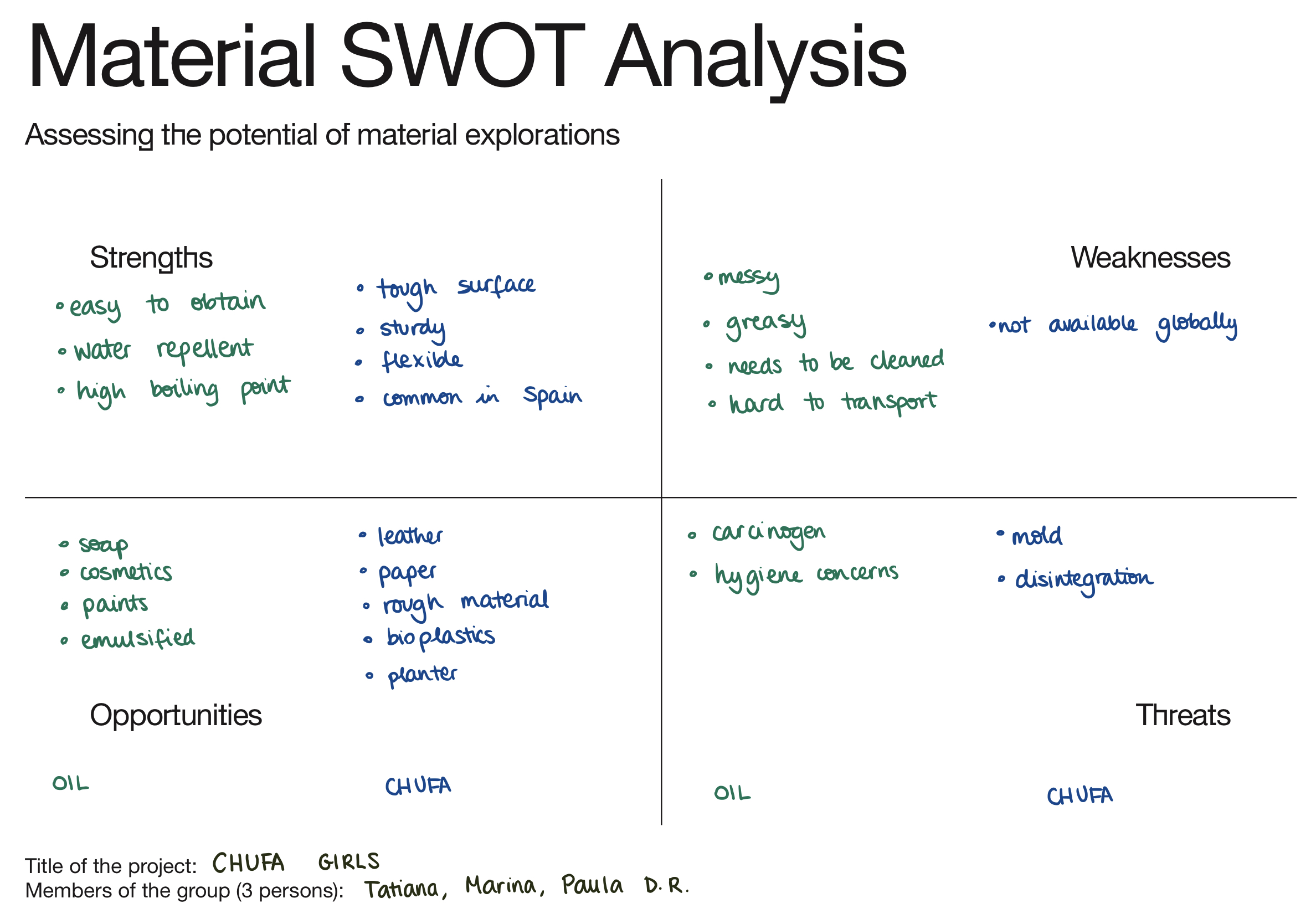

On Monday, we met up and explored the possibilities of using the chufa waste we collected the previous week. We noticed that the bag was warm and wet, and that the top of it began to mold. After scraping off the top layer, we gathered some from the center which was not yet going bad.

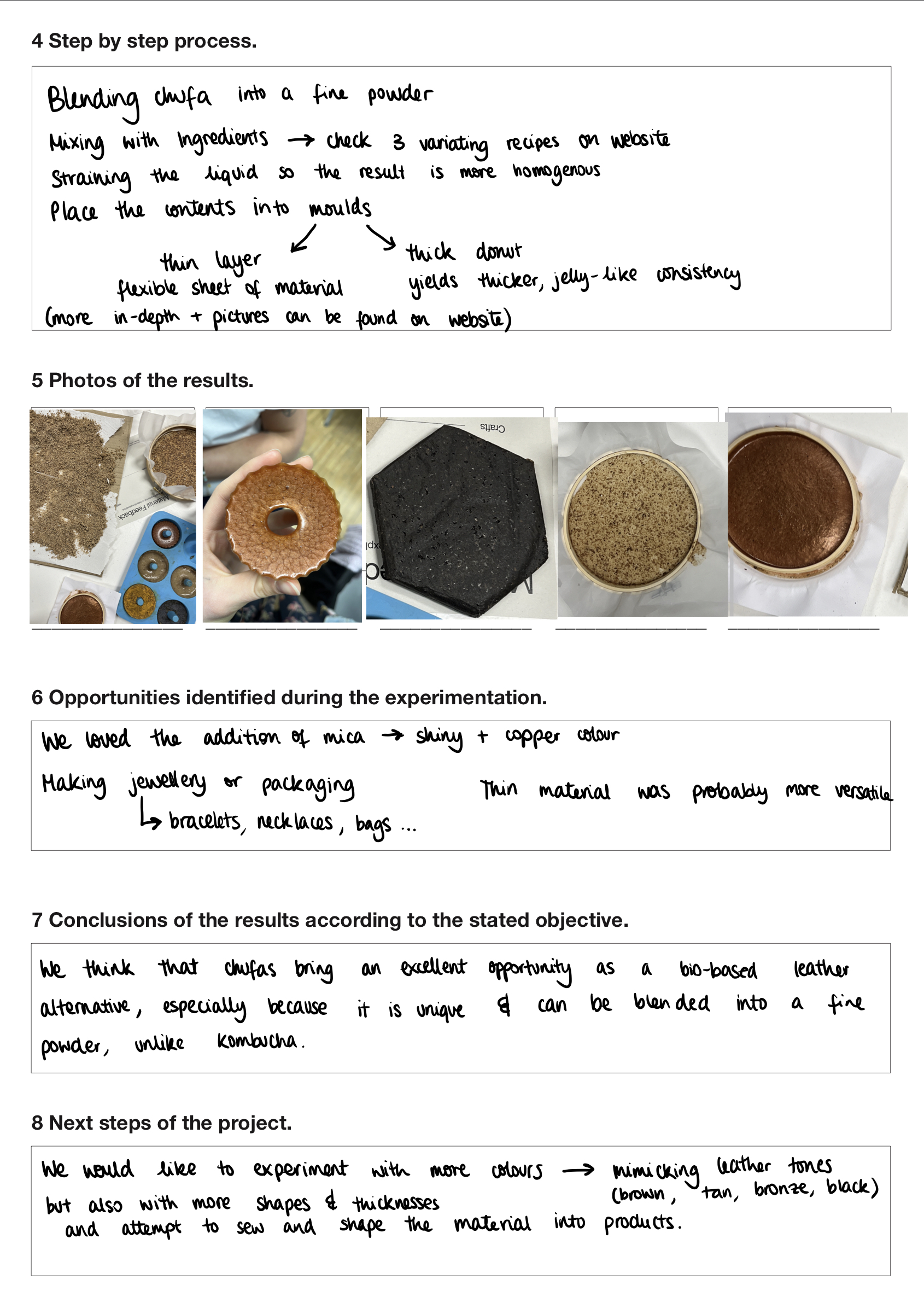

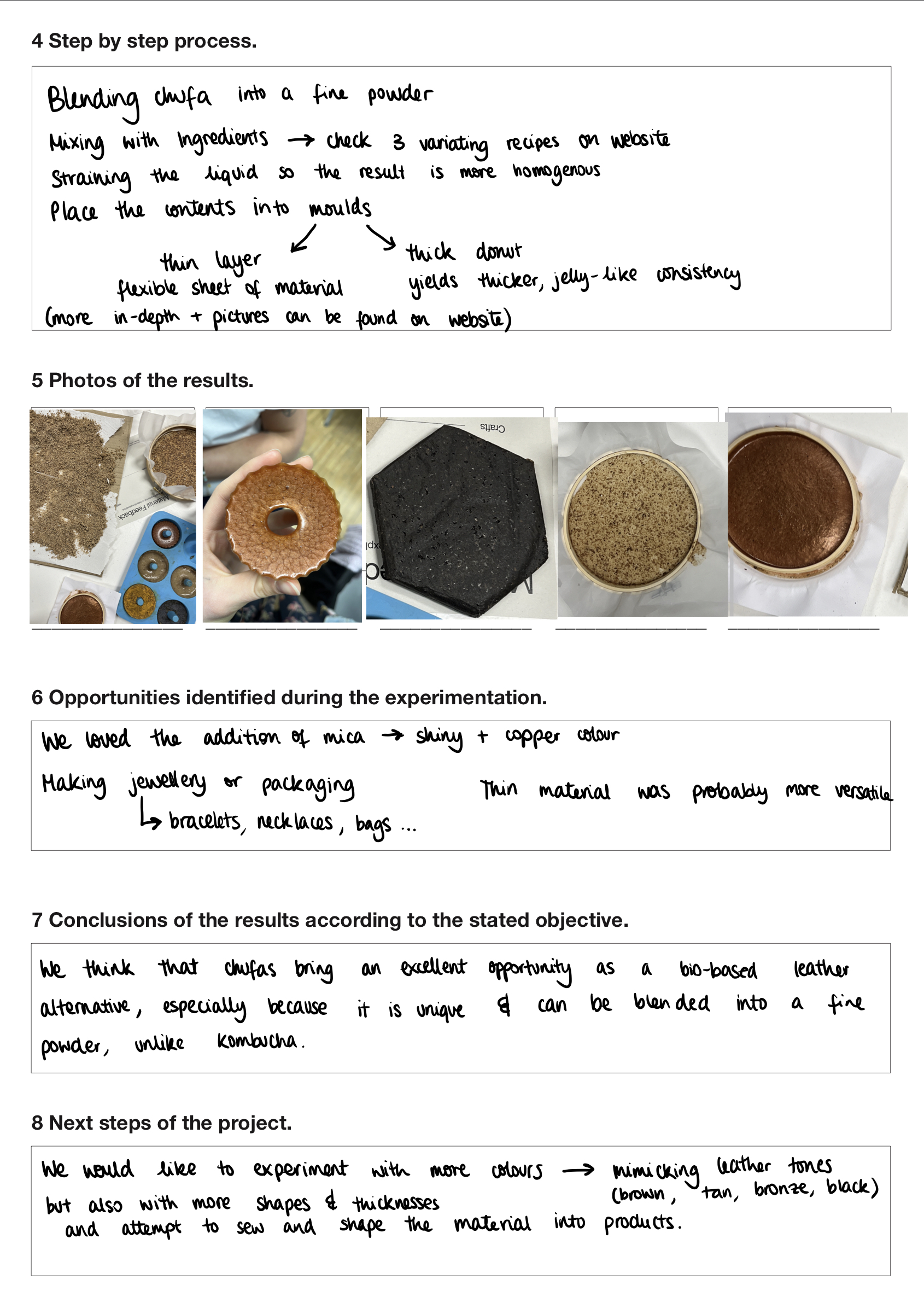

We began to experiment. We ground up the chufa into a finer meal, then seperated into different work stations, where each one of us used slights different ingredients and moulds. We wanted to see the different possible textures we could achieve according to the various techniques used.

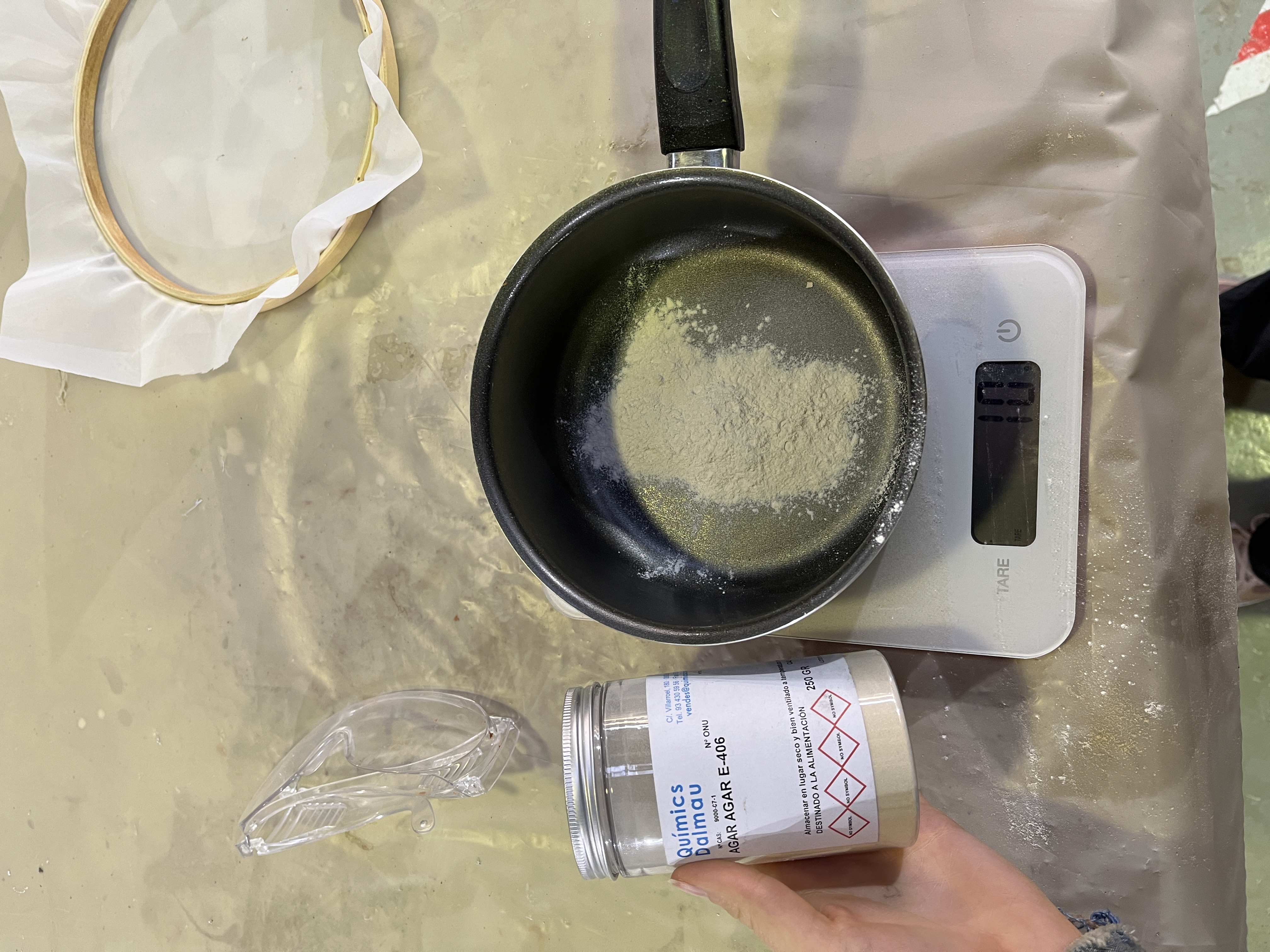

I personally made a mixture composed of alginate (10g), agar (10g), chufa meal (40g), glycerin (20g), water (300g) and a splash of vinegar.

Marina and I spread out my batch into a large, thin layer on the mould. We will see in a few days how it looks when it dries out.

6 Opportunities identified during the experimentation.

6 Opportunities identified during the experimentation.

Material Exhibition

On Thursday Feb 10, we exhibited our various biomaterials and went from table to table listening what other people had to say about their waste material experiments and final outcome. This was the full table:

I really liked the "beer paper" and the cemetery flowers comb idea, even though it didn't pop out of the mould fully.

These were the materials we displayed, and there was definitely a favourite amongst the crowd: The shiny, jellyfish donut Chufa + Mica biomaterial.

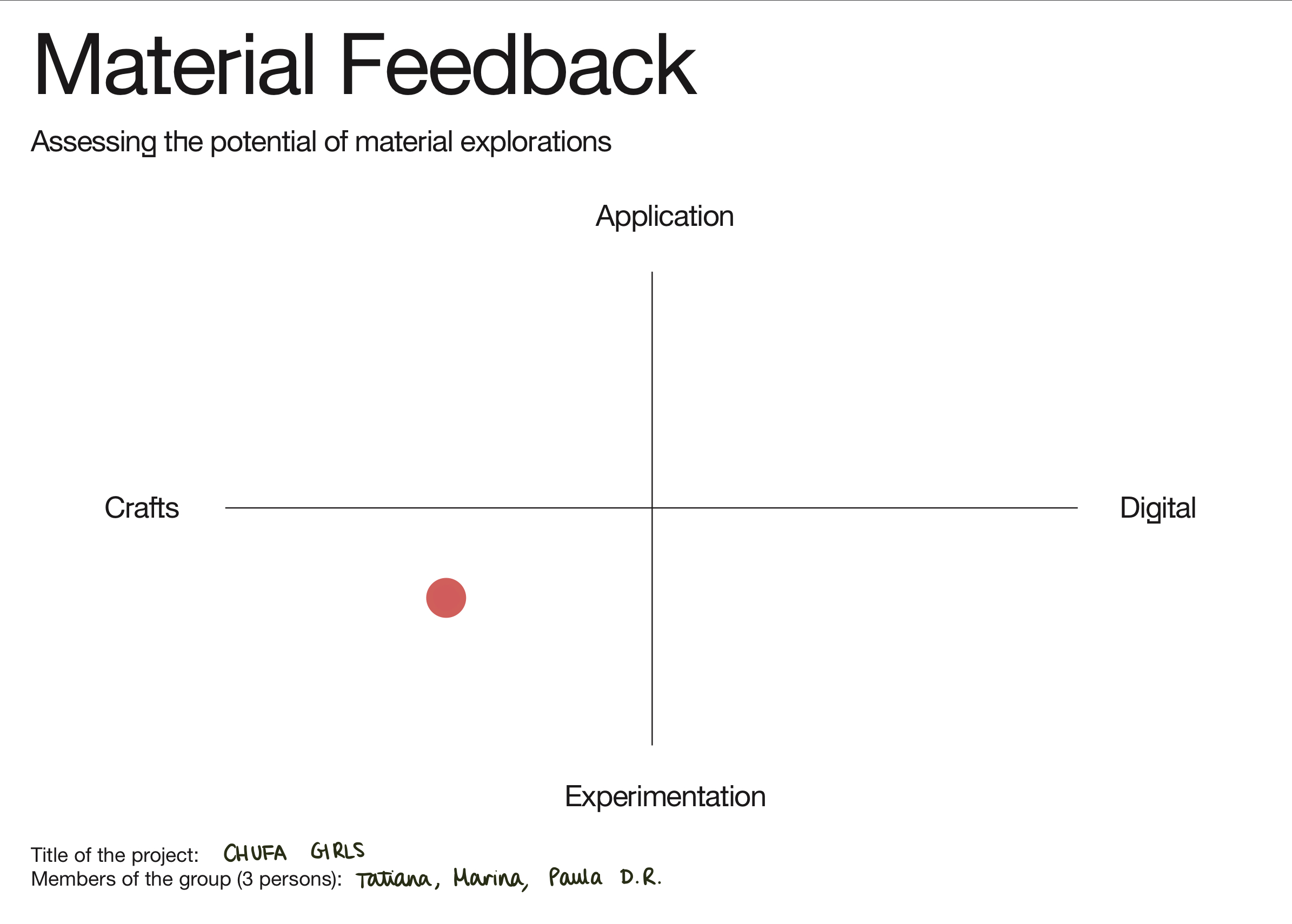

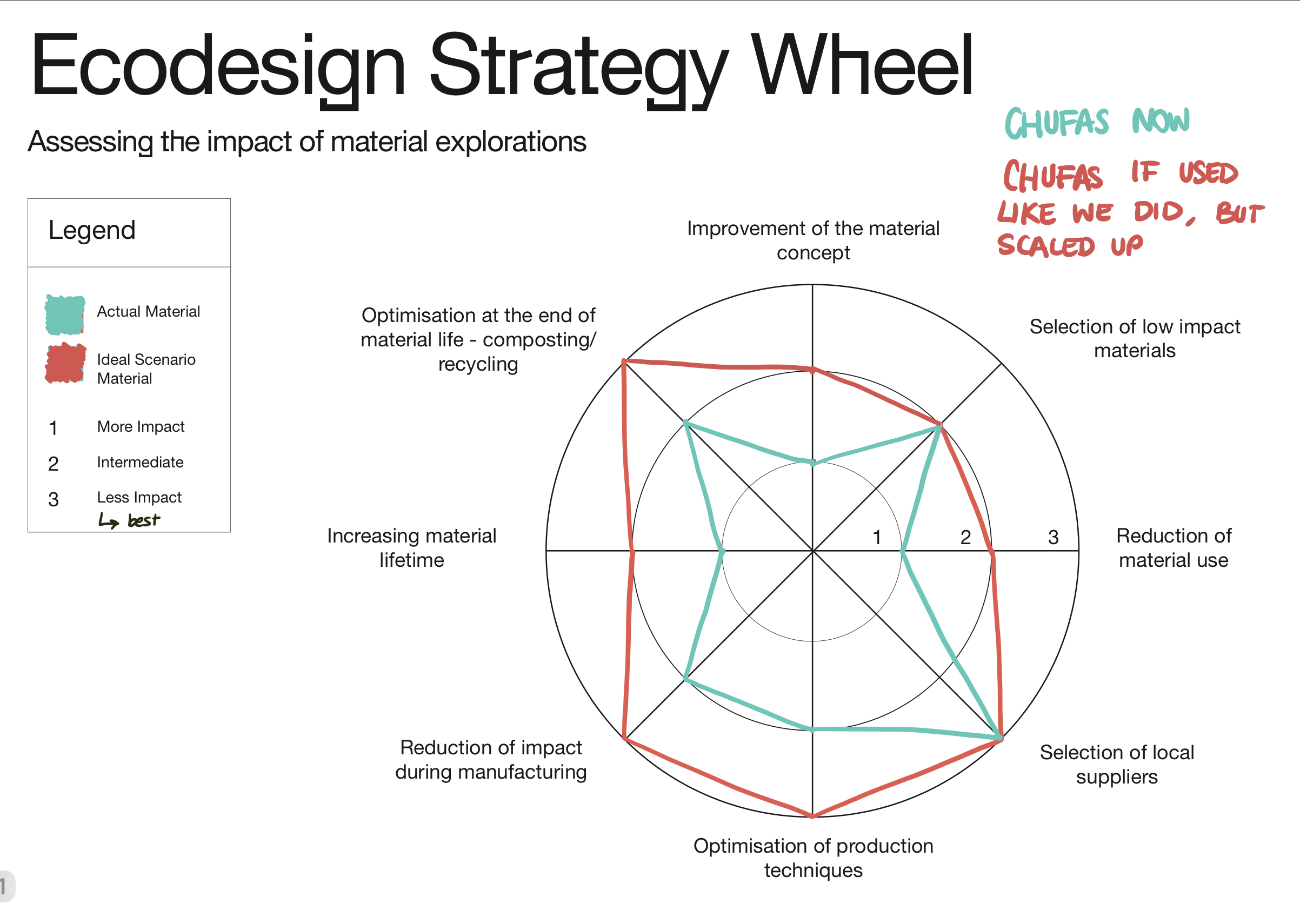

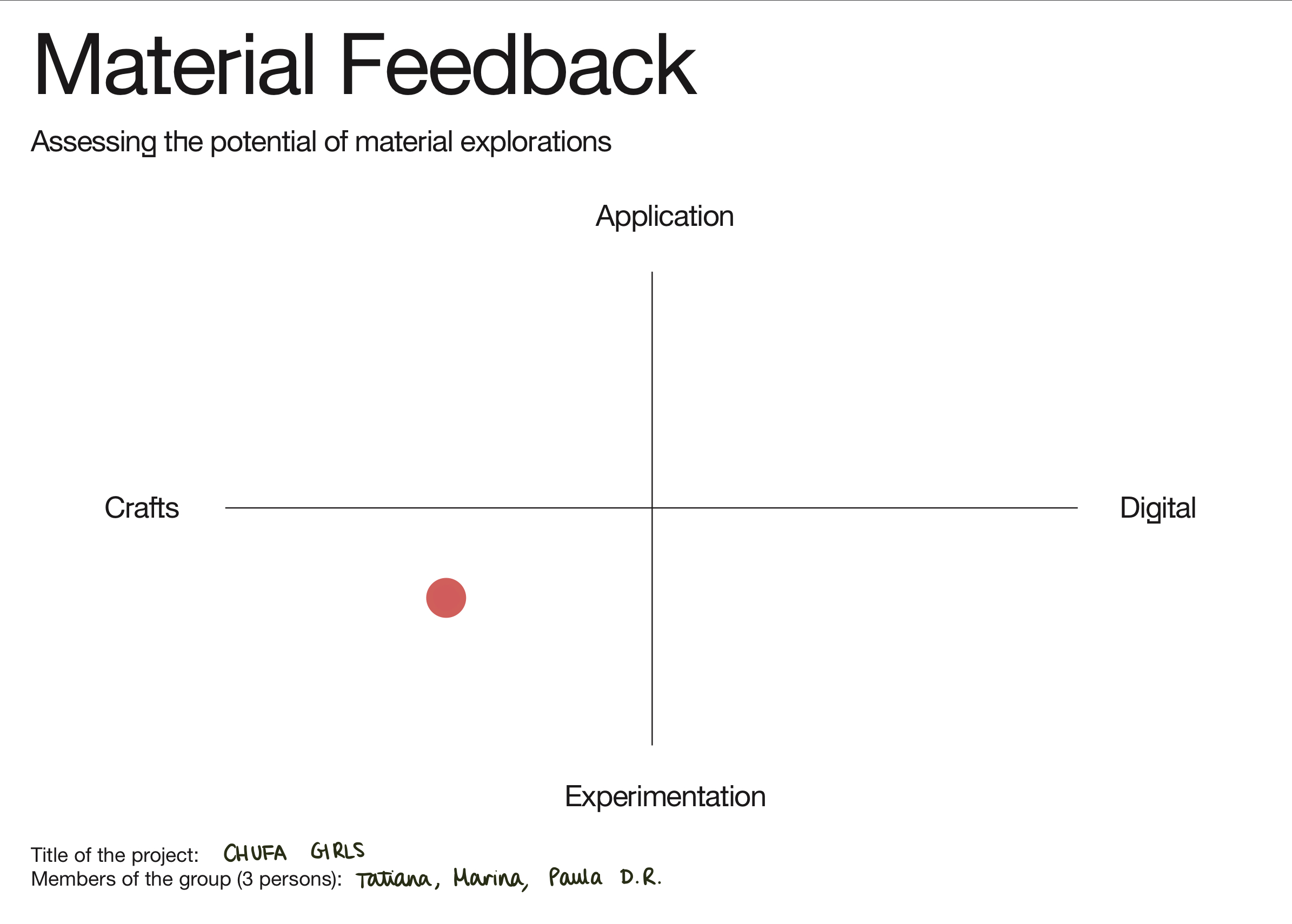

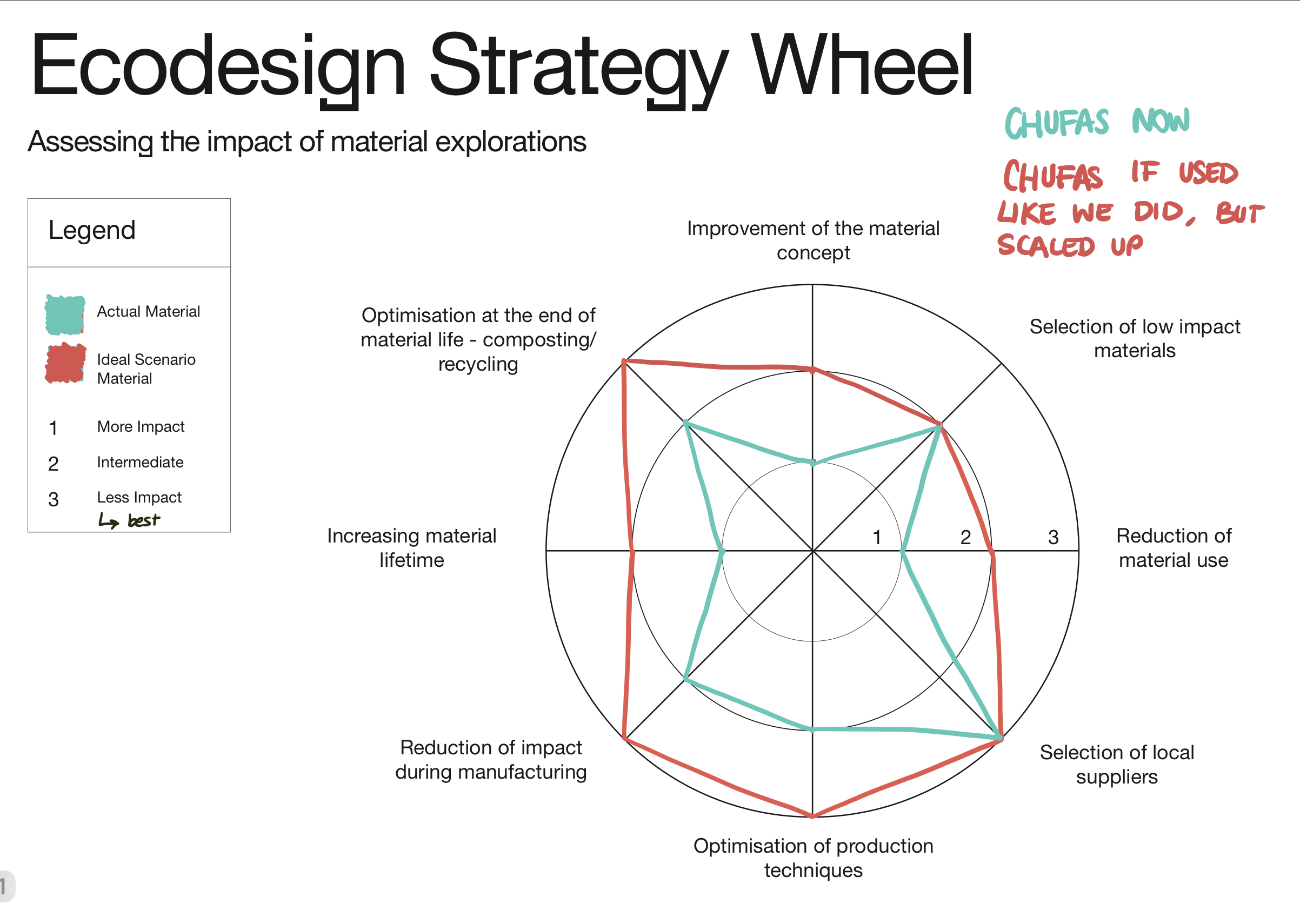

Last but not least, here is our completion of the pdf we were asked to complete by Sunday Feb 20th.

A)

The material, waste chufa (tiger nut), was sourced from a nearby horchateria called El Tio Che on the rambla in Poblenou. The chufa bulbs are squeezed and used to make the drink, and then the remains excreted by the machine are the waste product, which we decided to find a second use for.

B)

The chufa is the tuber of a plant. Because of this, it would theoretically be biodegradable depending on what other materials were added to it. The material is sourced locally in our nearby neighborhood. The chufa that the horchateria obtained was from Alboraia in Valencia so it is all local to Spain. The material is a smart choice economically because as it is a waste product, it could be used with little to no cost since most horchateria are throwing it away anyways.

C)

The material fits into a circular economy because first and foremost, it is sourced locally. It is a waste product so no new material is being added when it is being used as the main input into the biomaterials. By using the waste product, it is not allowing the chufa to become waste after being pressed but instead continuing its lifecycle into new products. If it were combined with other natural materials, it could be biodegradable, and therefore would not contribute to more waste.

D)

After doing some experimentation, we saw that the chufa could take a variety of forms and therefore uses. We felt that it could make a really good plant-based leather. It could also be used for tiles, decorative objects, textile, or even a replacement for a wood composite.

Currently, I am not aware of any industrial processes that use a material like chufa to create new products.

In order to industrialize the material, the collection process would first have to be streamlined. This means that horchaterias would have to collectively have their material placed or picked up at a collection center. This would be easiest in places where there are a lot of horchaterias, but with a single one in Poblenou it would not make sense to try to industrialize it from that location. The material would also have to work in a system where it could be dried quickly and in large quantities, removing any excess water from it as fast as possible so that it does not start to ferment or develop mold. The chufa came to us pre-ground, but ideally would have to be ground to a fine powder in order to create more even, uniform materials.

E)

We have not found any current industrial processes for chufa, neither for creating nor disposing of the Horchata waste. This means that our processes during the experimentation with the material are very different than the current standards. However, we did follow some basic biomaterial recipes and principles, so our experiments resemble lots of biomaterials typically using starches or other waste.

Chufas:

Chufas:

6 Opportunities identified during the experimentation.

6 Opportunities identified during the experimentation.